Shortly after taking over as the RBI Governor, Sanjay Malhotra deferred the implementation of the proposed Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) Framework from April 1, 2025, to ‘not before’ March 31, 2026. Banks had opposed the implementation earlier apprehending it would cause a liquidity crisis, and had raised the issue with the new Governor. They had also petitioned the government regarding the proposed LCR guidelines.

Not only in India but also globally, the implementation of the Framework, ab initio, has been riddled with issues. Several prominent researchers opine that, “Unlike capital regulation, which has received extensive academic scrutiny, liquidity regulation is new and has run ahead of research.” However, post-implementation, in advanced economies, a plethora of research has evolved, and it’s growing.

This piece endeavours to analyse some of the issues, rather briefly.

Framework in brief

Following the 2007-09 financial crisis, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) recommended bank regulators to adopt two liquidity standards: (a) LCR that enhances banks’ short-term liquidity resilience; and (b) the Net Stable Funding Ratio that promotes liquidity resilience over a longer time horizon.

Chiefly, the Framework mandates banks to hold sufficient stock of unencumbered High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLAs) that can be converted into cash easily and quickly to meet its liquidity needs under a 30-day liquidity stress scenario.

LCR = [(Total Stock of HQLAs)*100]/[Total Net Cash Outflows (NCOs) over the next 30 calendar days]

HQLAs are those which can be readily encashed or used as collateral to obtain cash in stress scenarios, and they comprise Level 1 and Level 2 assets. While Level 1 assets are with 0 per cent haircut, Level 2A and Level 2B assets are with 15 per cent and 50 per cent haircuts, respectively.

Total NCOs are the total expected cash outflows minus total expected cash inflows for the subsequent 30 calendar days.

Total expected cash outflows are calculated by multiplying the outstanding balances of various categories of liabilities and off-balance sheet commitments by the rates at which they are expected to run off.

Total expected cash inflows are calculated by multiplying the outstanding balances of various categories of contractual receivables by the rates at which they are expected to flow in up to an aggregate cap of 75 per cent of total expected cash outflows.

Is LCR new?

As per an IMF Working Paper (2019), “…liquidity ratios similar to LCR were commonly used as monetary policy tools by central banks between the 1930s and 1980s.” Further, reserve requirements in the US existed even in 1837, says an US Fed article (2013).

Some academicians term LCR as a ‘sophisticated and complex’ form of the liquidity ratios similar to the above. Some even state that LCR is based on internal ratios normally used by banks.

Effectiveness of LCR

The Framework was tested during the March 2023 banking turmoil in the US and Euro area when actual deposit outflows for the affected banks in the US (mostly uninsured deposits) and Switzerland (mostly non-financial corporate deposits) were significantly higher than the LCR cut-off assumptions for these deposits.

As per the BCBS report on the turmoil, Silicon Valley Bank lost 85 per cent of its total deposits over two days; and for First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse total deposit outflows stood at 57 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively, over 90 days.

The Indian scene

The RBI issued the Indian Framework for LCR requirements on June 9, 2014, for all scheduled commercial banks (excluding Regional Rural Banks — RRBs). Introduced in five phases starting January 1, 2015, the minimum LCR requirement stipulated by RBI is 100 per cent since January 1, 2019.

With their establishment, Small Finance Banks (SFBs) came under the Framework. Currently, the Framework excludes RRBs, Payments Banks and Local Area Banks.

The RBI Draft Guidelines released on July 25, 2024, require banks to: (a) assign additional five per cent run-off factor for retail deposits enabled with Internet and Mobile Banking (IMB) facilities; and (b) treat unsecured wholesale funding from non-financial small business customers in accordance with the retail deposits as at (a).

As already mentioned, the implementation is now deferred by a year.

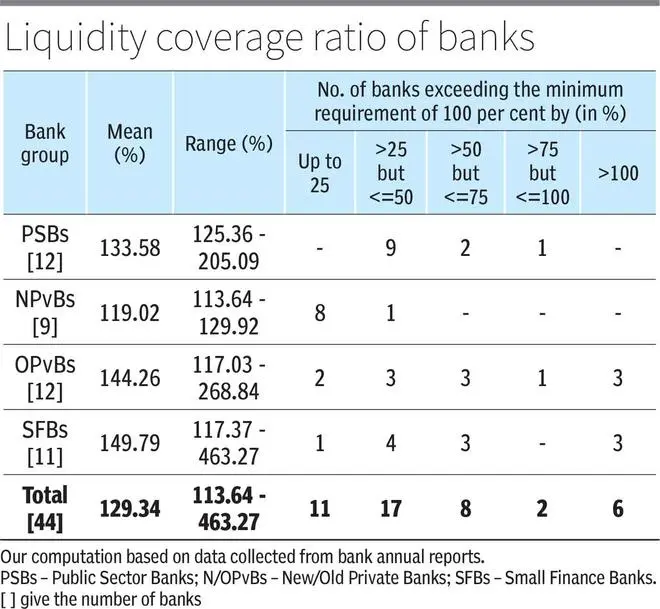

The Table presents LCRs for four bank groups comprising 44 banks for the quarter ended March 31, 2024. The 44 banks reported LCRs exceeding the minimum requirement of 100 per cent. However, the bank annual reports provided no reason thereto. The smaller banks (SFBs and OPvBs) reported higher means and ranges compared to their larger counterparts. For the 44 banks together, considering the averages of the weighted values, ‘unsecured wholesale funding’ and ‘retail deposits and deposits from small business customers’ together accounted for 74.2 per cent of the cash outflow. Similarly, the cash inflow principally came from ‘inflows from fully performing exposures’ (68.8 per cent).

Classifying only ‘transactional’ accounts under ‘stable’ deposits is, however, not clearly understood. In Indian banking, transactional accounts are generally understood to include savings and demand deposits accounts and exclude time deposits accounts. However, time deposits are more stable than the former two account-types. And, deposit insurance covers time deposits as well.

Additional weights for retail deposits with internet/mobile banking facilities run contrary to the national goal of a less-cash economy. These factors taken together lead to the question of whether LCR is overestimated.

Universal issues

Some of the areas that need intensive theoretical and empirical research globally as also in India are:

Why do banks tend to hold liquidity buffers above the minimum requirement?

The interaction of the liquidity regulation with the monetary policy implementation. Besides its prudential role, whether LCR can be a monetary policy tool to promote financial stability?

Since higher liquidity ratios reduce the quantity of assets banks can use as collateral, credit supply of the banking system reduces. Will this dampen economic activity?

In India, does SLR essentially serve the same purpose as LCR?

Should LCR and the central bank’s Lender of Last Resort function co-exist to forestall liquidity crises?

Should the Framework apply to all banks irrespective of their sizes, deposit portfolios, etc.?

In sum, there are “miles to go before” the Framework is seamlessly implemented.

Das is a former senior economist, SBI. Rath is a former central banker. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.