Highway to Hell: Inside PennDOT’s Plan to Widen I-95 Through South Philly

Everyone knows the construction of the interstate along the Delaware River waterfront 60 years ago was a catastrophe of urban planning. So why is the state planning to make the road even bigger?

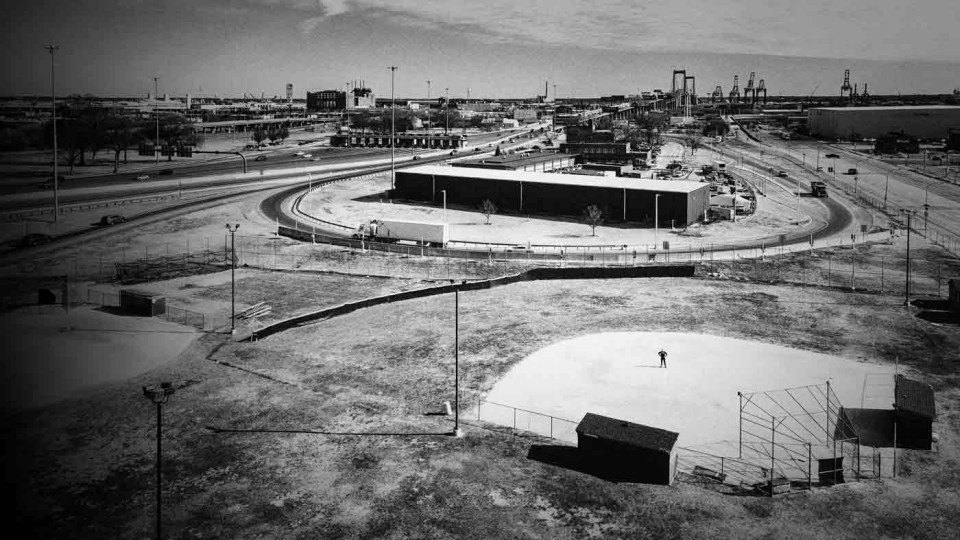

The I-95 expansion will change the landscape of Philadelphia neighborhoods. / Photography by Kyle Kielinski

The Southeast Youth Athletic Association is wedged into a small square block in South Philly. On some level, the location is fitting: From the blacktopped parking lot, you can see the lights from Citizens Bank Park peeking out in the distance a few blocks away. But if the field for the professionals dominates its surroundings (which is to say its parking lots) like a church looming over a plaza, SEYAA’s fields feel as though they’re boxed in on all sides. To the north is Bigler Street, with its line of modest rowhomes; to the south, there’s the rumbling stretch of the Schuylkill Expressway. To the west are the four lanes of 7th Street and an off-ramp for the highway, while to the east there’s a shopping plaza and a set of vermicular highway ramps leading to and from the Walt Whitman Bridge and Interstate 95.

All told, there are five fields at SEYAA: two youth baseball fields with 60-foot basepaths and one 90-foot regulation-size baseball field, plus two additional spaces that are used for soccer, flag football, and T-ball, depending on the season. Upwards of 1,000 kids participate in SEYAA’s various leagues, which run nine months of the year and cost between $35 and $90 to join. Joann McAfee, the 61-year-old volunteer leader of the league, has been overseeing the programming in this unique stretch of open space in deep South Philly for nearly 30 years.

Housed on land owned by the Delaware River Port Authority, the entity that controls the nearby Walt Whitman Bridge, SEYAA’s facilities have long had a scrappy quality to them. According to Mark Kapczynski, the president of Whitman Council, the civic association serving the neighborhood, the site containing the fields used to be a construction dump. Four years ago, when SEYAA secured a grant for new lighting — some of the old lights having been salvaged from the demolition of JFK Stadium in 1992 — the contractors found heaps of debris buried beneath the ground. Although the sports franchises contribute a total of $1 million annually to a special services district meant to improve the neighborhood surrounding the stadium complex, the fields sit on the wrong side of the district’s border, shutting them off from a potentially lucrative revenue source.

Kapczynski, who’s 64, played baseball on these fields as a kid. “This was a haven,” he says. As an eight-year-old, he would walk from his home on Ritner Street to the fields, which seemed like a kind of paradise set off from the city. These days, Kapczynski sees the fields a bit more pragmatically. “Our facilities are terrible,” he says. The grass is patchy and often unkempt. A fading Coca-Cola sign that looks like it could be from Kapczynski’s playing days looms over the wind-swept outfield from a forlorn scoreboard. The predominant view is of cars zooming along the nearby highway and the drab gray rectangle housing the Live! Hotel and Casino. In 2023, Kapczynski began to develop a master plan for the SEYAA facilities and a neighboring set of fields on the other side of the Schuylkill Expressway run by the Delaware Valley Youth Athletic Association. “I’ve always had this dream,” he says, “of pulling up to those fields and seeing the beauty you see at athletic facilities in West Chester, in Marlton, in Mount Laurel, up in Bucks County.”

Recently, Kapczynski was forced to consider a different scenario. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation has been engaged in a decades-long plan to reconstruct I-95, which is more than 60 years old and approaching the end of its engineering lifespan. The multibillion-dollar project, which has already begun farther north in Fishtown and Port Richmond, might have been an opportunity to reimagine a stretch of roadway that demolished homes and cut off the city from its waterfront, leaving a scar running down the city’s eastern edge for decades. Instead, when PennDOT released its plans for the section of the highway running from Penn’s Landing to South Philly in the fall of 2023, it became clear that the agency had other ideas. Not only did PennDOT want to make the highway wider, it was also planning to add multiple new on- and off-ramps — including on Wharton Street and down near the SEYAA fields. A wave of community outrage soon followed, stretching from Society Hill to Queen Village to Pennsport to Whitman.

But arguably no neighborhood has been angrier than Whitman. When Kapczynski looked at a map of PennDOT’s proposed changes, he could hardly believe what he was seeing: One of the new ramps was going right through SEYAA’s fields. Kapczynski had imagined pulling up in his car to verdant grass, with brand-new basepaths, dugouts, and fencing; he hadn’t considered the possibility that he would be driving his car on the fields themselves. “Their plans,” Kapczynski says, “will drive a stake right through the heart of these baseball and athletic facilities.”

At 1,917 miles, Interstate 95 is the sixth-longest interstate in the country. Beginning in Miami, it plows its way up the entire eastern edge of the United States, passing through every major city in the Northeast, before ending when there is no land left to conquer: at the Canadian border. Construction on the roadway in Philadelphia began in 1959 at a cost of $200 million — or more than $2 billion today.

If you have spent any time along the Delaware River waterfront — or spent time trying and failing to access that waterfront — then you know how the story ends. Despite major local opposition to the proposed path through multiple residential neighborhoods, the highway was built, ultimately severing the city’s connection to the river and resulting in the demolition of thousands of homes, including some 2,000 in the Southwark neighborhood. While neighbors protested up and down the eventual I-95 corridor, only well-connected Society Hill managed to limit the damage by getting the highway to be built beneath the street grade. (Early plans, mercifully never realized, also called for I-95 to intersect with the so-called Crosstown Expressway, a different highway that would have replaced South Street, essentially enclosing Center City within a prison of highways.)

These days, I-95 occupies a peculiar position. It is an omnipresent reminder of bad policy: a vehicular coup over the neighborhood, despite the fact that one of the central features of living in a dense city is being close enough to things that there’s no need to drive to them at high speeds; a health burden for nearby residents, who are forced to live with elevated levels of pollution; and a concrete eyesore that effectively serves as a giant barrier impeding access to the Delaware River. In South Philly, much of the area underneath the highway is made up of chain-link fencing and parking lots.

Yet at the same time, little pockets of community have cropped up under the highway, like a shipwreck slowly turning into a reef. At Washington Avenue, there’s the Rizzo Rink, an ice skating and hockey facility that’s been underneath the highway since 1979 in the space between two support pillars. (Occasionally, crumbling concrete from above falls onto the benches next to the ice.) Just south of the rink, there’s a makeshift skate park and three basketball hoops hanging from the underside of the elevated highway. Walking around these areas, it can feel as though the highway has receded into the landscape, as if it were part of the natural order.

These facilities’ days are numbered; when I-95 is rebuilt, they’ll have to be removed. But instead of ceding space to the highway over and over for eternity, there are entire agencies dedicated to reversing this state of affairs and reconnecting the city to its waterfront. Chief among them is the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, a nonprofit created by the city in 2009 to essentially undo the urban devastation wrought by I-95. On a small scale, the DRWC has overseen landscaping improvements to the long stretches of space underneath the highway; more ambitiously, it is currently engaged in a project to make part of the highway disappear altogether: The $440 million Penn’s Landing Park will see the highway between Walnut and Chestnut streets capped and covered with a waterfront park that will run all the way from Front Street to the river. PennDOT has been supportive of the project, and indeed much of the cap park’s funding comes from the federal highway dollars PennDOT is using for its broader I-95 reconstruction.

The cap project would suggest, in other words, that a sort of consensus has emerged with respect to I-95: Make the highway as less-bad as possible. Current PennDOT secretary Mike Carroll has called the construction of the highway an “original sin.” The I-95 project represents a rare shot at redemption: a once-in-a-generation opportunity to not just rebuild the highway as it is today but fundamentally reimagine it for decades to come. Which is why it’s all the more surprising that the very same PennDOT involved with the cap park is proposing what seems to be a completely incompatible project right next door.

The Southeast Youth Athletic Association fields in South Philadelphia

PennDOT unveiled its vision for the so-called Central to South Philadelphia section of I-95 through an online survey in September 2023. Bizarrely, the survey was embedded within a virtual-reality “room,” which featured wood-paneled ceilings and Sims-esque characters standing around various poster boards with information about the redesigned highway. Users could navigate through the room as though they were playing a video game, and eventually, if they succeeded in advancing far enough, they’d reach the final boss: the actual survey.

The whole purpose of the survey was ostensibly to garner feedback from the community, yet PennDOT initially allowed just three weeks for people to comment on the plans. (The department later extended the comment period an additional two weeks after community pressure.) It apparently did little to inform residents of the survey ahead of time, either. Kapczynski, who as president of a civic association can reasonably be counted in the top one percent of engaged citizenry, says he learned about the proposals through the newspaper. “We were blindsided by this announcement from PennDOT,” he says. “Blindsided.” Nor did PennDOT share its plans with elected officials. State Representative Liz Fiedler, whose district includes the stretch of highway passing by the ball fields, didn’t know PennDOT had released a plan until a staff member brought it to her attention after attending a routine meeting of the Sports Complex Special Services District. “I was very frustrated that we learned about it that way and not in a more official way,” Fiedler says.

The virtual room revealed that PennDOT’s proposals centered on three stretches of highway: Penn’s Landing (the area between the under-construction cap park and McKean Street), the Walt Whitman Interchange (the area covering the SEYAA ball fields, where I-76 meets I-95), and the Broad Street Interchange (the area farther south where I-95 intersects with Broad Street near FDR Park, the stadiums, and the Navy Yard). For each section, PennDOT proposed low-, medium-, and high-impact designs. PennDOT made little secret of where its own preferences lay; in one video, a narrator introduced the high-impact design by saying that “the high-build design concept is intended to satisfy the future traffic needs of the region and the key economic drivers in the area” — the implication being that any other version of the plan would naturally fall short.

For the community members viewing the plans, much of the confusion stemmed from PennDOT’s seemingly incompatible set of goals for the project. In one part of the virtual room, PennDOT stated its desire to “fit I-95 into its urban context”; in another section it described the project as a “reconstruction and widening of the highway.” (The agency proposed increasing the number of lanes from three to four to “ease congestion.”) In a section for the Whitman Interchange, PennDOT noted a goal of “preserving DRPA ball fields as an important South Philly community resource.” And then in each of the three different renderings for the Whitman Interchange there was a road running straight through those very same fields.

On a Thursday night in June, PennDOT held an in-person meeting at the Edward O’Malley Athletic Association in Pennsport. The meeting, which had been scheduled after pressure from various civic associations as well as elected officials, wasn’t fully open to the public; it was intended only for civic association leadership. At the meeting, a procession of people expressed their displeasure with PennDOT while the highway officials took notes. Kapczynski shared that SEYAA, thanks to a donation from Live! Casino, had recently secured $100,000 worth of new lighting, and that he was in the early stages of crafting a master plan for the fields. “They had no idea what we were doing down there,” he says. “Not a clue that an organization has stepped up finally to give funding to make significant improvements and to establish those fields as quality athletic facilities for the kids of South Philadelphia.” McAfee, the volunteer leader of SEYAA, broke down crying as she described the impact the redesigned road would have on the fields she’s spent half her life maintaining. The PennDOT representatives emphasized that the plans weren’t set in stone and that there was plenty of time for the designs to change by the time construction was scheduled to begin in the late 2030s. (A PennDOT official later suggested that Kapczynski try to secure historic designation for the fields since they’ve been in operation for decades. “Not to sound like a complete tool, but that may have been the only constructive thing that came out of that presentation,” Kapczynski says.)

Next, the PennDOT officials shared the results of the survey. When asked to choose between the low-, medium-, and high-impact designs, a plurality of respondents had selected “none” for both the Penn’s Landing section and the Broad Street Interchange. This seemed to comport with the displeasure everyone had just articulated at the meeting. But when it came to the Whitman Interchange proposals affecting the baseball fields, PennDOT claimed that 50 percent of respondents preferred the high-impact scenario, which sees a new on-ramp starting right around home plate of SEYAA’s largest field before looping down the third-base line and through the outfield to connect to I-76 West.

A few weeks later, an independent blogger named Megan Shannon submitted a public records request to PennDOT for the data underlying the survey. While PennDOT claimed that had it recorded 652 responses to the Penn’s Landing survey, 736 for the Broad Street Interchange, and 1,025 for the Whitman Interchange, it turns out that those weren’t the true numbers; they were simply the number of page views for each plan. The number of people who actually completed the survey, according to the data, which Shannon posted on her website, was much lower. While PennDOT had implied that 1,025 people left feedback on the Whitman Interchange, for instance, the data shows that there were just 132 unique responses.

In truth, the PennDOT survey was flawed in deeper, more fundamentally embarrassing ways. Though the agency had presented a percentage breakdown of the “overall concept preferences,” there wasn’t actually a question asking people which option they preferred overall. Instead, there were three separate questions asking which concept people preferred when it came to “impact on safety and congestion,” “impact on connectivity and multimodal services,” and “impact on socioeconomic, cultural, and natural resources.” To generate the figures for the supposed overall concept preferences, PennDOT simply tallied up the responses to all three questions and combined them.

Making matters worse, from a statistical perspective, the survey was designed in such a way that people could choose options for “low,” “medium,” “high,” or “none” — or they could simply not pick an option at all, which in the data is recorded as “select.” For the Whitman Interchange, this “select” nonresponse response was the single largest group in the entire survey: 251 in all across the three questions. (The next highest total was for “high,” which had 72 responses.) In compiling its figures, PennDOT eliminated this group from its dataset altogether, even though the vast majority of people who failed to register a response clearly opposed the project, because they left comments saying exactly that. Joann McAfee was one such person; she left a signed, detailed comment explaining exactly how all three plans would destroy the fields. Or you could take it from a different respondent, whose preference was not recorded in the survey results either: “DON’T FUCKING RUIN ALL THIS LAND TO MAKE YOUR DAMN ROAD BIGGER.”

If you actually attempt to use the data to glean a meaningful sample of community preference, what you start to see is something that looks a whole lot different than what PennDOT presented to the community. Even using PennDOT’s (flawed) methodology combining the responses to all three survey questions to generate an overall preference for the Whitman Interchange, a new picture begins to emerge.

Fifty percent of people did not support the high-impact concept; 18 percent did. The medium- and low-impact designs garnered one and two percent support, respectively. And what about the group who chose “none” or failed to make a selection?

Seventy-nine percent.

Community members were wary of PennDOT even before the survey fiasco. “This isn’t our first rodeo with I-95 coming through our community,” Kapczynski says. Many residents are just one generation removed from the highway’s initial construction. “Everybody seems to have a story about their aunt, their grandmother, whose home was taken by eminent domain,” says Mary Purcell, a board member of the Society Hill Civic Association who’s been one of the leading forces opposing PennDOT’s engagement process. Kapczynski’s mother’s family lost their home due to the highway’s construction. So, too, did the mother of Patrick Fitzmaurice, the president of the Pennsport Civic Association. “She’s still in Whitman,” Fitzmaurice says. “She remembers. She still has paperwork from when eminent domain took her house.” Considering the history, it was always going to be an uphill battle for PennDOT to gain the community’s trust. And that was before they unveiled their plans for a bigger highway and misrepresented data.

After the survey meeting, the leaders of the nearby civic associations held their own gathering to discuss their vision for the highway. They were, in effect, enlisting themselves to do the community outreach they felt PennDOT had failed to perform. Society Hill hired a transportation consultant to draw up a set of priorities. “This was not a study for what should be done with 95 or where ramps should be or removed or anything like that,” Purcell says. “This was first principles: If you’re coming here to design a highway, you need to understand general principles about what the community is concerned about so that you bake that in from the start.”

While the various neighborhoods have been working together on this plan, some key differences remain between them. For one thing, the level of antipathy toward PennDOT seems to be closely correlated with proximity to the highway. Purcell, in Society Hill, says she doesn’t have a negative view of PennDOT. “Our role here is pushing that the community engagement has to be integrated right from the start and throughout,” she says. In Pennsport, Fitzmaurice isn’t buying PennDOT’s line that the plans are subject to change. “I’ve said from the beginning, why have the survey, and why have these high-, medium-, low-impact plans, if your intent wasn’t to move forward with one of them?” he says. Down in Whitman, Kapczynski is even less charitable. He believes PennDOT’s motivations have little to do with traffic and are really about facilitating development for powerful forces nearby: the Port of Philadelphia; the Navy Yard; the sports complex, where the Sixers and Comcast will soon be building a new arena; and the Bellwether District, a $4 billion redevelopment of the former Philadelphia Refinery site into a shipping and logistics center. Kapczynski says he’s cooking up a scheme to revise his master plan in the hope that it will somehow prevent PennDOT from taking over the fields: “I’m going to use that as a sledgehammer over PennDOT’s head.”

Joann McAfee and Mark Kapczynski

The strange thing about PennDOT’s plans for South Philly is that there is some precedent for modern, forward-thinking PennDOT projects that aren’t totally car-centric. In Port Richmond and Fishtown, where the I-95 reconstruction project began years ago, PennDOT has worked with the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation to replace the chain-link fencing underneath the highway with a landscaped pedestrian and bike trail that weaves through parking areas and public art installations. PennDOT is also researching, after lobbying from advocates, the feasibility of building a subway beneath Roosevelt Boulevard in the Northeast.

But according to transportation policy observers, there is a critical distinction between PennDOT’s fundamental highway project parameters, which are often bad, and the ancillary projects they tack on, which are often good. The cap at Penn’s Landing can be seen in this light. “PennDOT to my understanding has been a great partner and part of this,” says Matt Ruben, the chair of the Central Delaware Advocacy Group, a community organization helping to advance DRWC’s master plan for the waterfront, “but this does not spring out of PennDOT’s culture of highway reconstruction at all.” PennDOT didn’t begin its I-95 reconstruction with a plan for the cap park; the reason the cap is happening is because the DRWC advocated and fundraised enough to actually put the project on the table.

Ultimately, Ruben contends, to focus solely on improving the highway’s surroundings is to miss the point. “If your new on-ramp has nice-looking retaining walls with landscaping all around it, that’s much better than it would have been when they originally built the highway,” he says. “But if that on-ramp destroys your community’s athletic fields or other important community infrastructure and creates a wider barrier between you and the waterfront, then that’s just putting lipstick on a pig.” And the biggest problem when it comes to PennDOT, Ruben says, is that their “process is geared primarily, in my opinion, to talking about the lipstick. And we need to talk more about the pig.”

I meet with Secretary of Transportation Mike Carroll over videoconference in early January. Carroll, a fast-talking former state representative from Northeastern Pennsylvania with a no-nonsense demeanor, sits in front of a map depicting all of the roadways in Pennsylvania. From a Philadelphia perspective, Carroll is an ideal kind of leader for a state agency. His background as a House Democrat from just outside Scranton means he doesn’t suffer from the common Harrisburg affliction of hating the population centers that produce much of the state’s tax base. He has positive working relationships with State Representative Liz Fiedler and State Senator Nikil Saval, and they in turn speak fondly of him.

One theory of PennDOT’s behavior is essentially Darwinian: The agency needs funding to survive, and will therefore prioritize expensive projects that inevitably involve building more roads. While today’s PennDOT may not be behaving like transportation departments in places like Texas, where the DOT is currently doing its best 1960s impression with a plan to expand I-45 in Houston through eminent domain, it is not exempt from this fundamental dynamic. “There is a question of who is benefiting and who wants this,” Erick Guerra, a planning professor at Penn’s Weitzman School of Design, says of the I-95 project. “I’m not sure who really wants this. The DOT wants it.”

Carroll rejects this line of thinking. “To say we’re a road- and bridge-building agency is not a sentence that’s long enough,” he says. “We’re a road- and bridge-building agency that also provides transit financial support across the state.” As evidence, Carroll points to the $153 million PennDOT rerouted, upon direction from Governor Josh Shapiro, from various road projects to stave off SEPTA’s looming budget crisis.

But if PennDOT’s vision for I-95 isn’t born of some innate drive to expand highways, how else are we to understand the project? From Carroll’s perspective, the plans are provisional and the community uproar represents the process playing out as intended. “The very conversation in the community that’s been generated is exactly what we’re hoping for,” he says.

The problem with this theory is that, for starters, PennDOT couldn’t even manage to accurately render the voice of the community with its survey results. And while Carroll calls the current plans for the highway “nowhere baked,” that isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement of his department’s work ethic: The design for this section of the highway has been underway since 2016.

Carroll contends that the central goal of the I-95 project is about safety — essentially, widening the highway’s shoulders to keep people safe when their vehicles break down. “We’re really not adding capacity to 95 here,” he says, though this seems to directly contradict PennDOT’s own plans that describe adding lanes to ease congestion. If there are no capacity concerns, then why does PennDOT cite, by way of justification for the designs, an estimated 10 percent increase in traffic by 2045? And how, exactly, does shoulder-width safety explain adding new ramps? When I ask Carroll to comment on the high-impact design scenarios with new ramps, he seems hesitant to engage on the specifics. “Whatever this high design is, or whatever you’re looking at, again, it is nothing that is finalized,” he says.

Underneath I-95 in Pennsport

One possible explanation for the apparent disconnect is that, for transportation departments, safety is often conflated with expansion. That’s Guerra’s interpretation. “What’s considered to be safety corresponds really well to expanded capacity, wide lanes,” he says. Sure enough, a PennDOT spokesperson says the proposed new lanes “would not be through lanes for additional traffic” and instead would be a measure to help drivers get on and off the highway more safely. Whatever the rationale, the result is the same: a wider highway with more lanes. (Transportation planners almost universally agree that more lanes won’t even solve a congestion problem: Once you add lanes, countless studies have shown, more cars show up, nullifying any traffic improvements.)

For people living in Whitman, though, the most important question isn’t about transportation policy semantics or even justifications. It’s about what will happen to the fields. Carroll insists that his agency has heard the feedback emphasizing their importance. “We get it,” he says. “And, you know, there are solutions to that that preserve — maybe even enhance — the ball fields in that area.” But based on PennDOT’s numerous murky explanations so far, you could forgive Whitman residents for not holding their breath.

What would a better version of I-95 look like? In 2022, Jeffrey Brinkman and Jeffrey Lin, two economists from the Philadelphia Fed, proposed a solution that on its face seems outlandish: burying the entire highway from Girard Avenue to Snyder Avenue. The idea’s central concept is that neighborhoods closest to urban highways often benefit the least. A highway might help someone get to the city; it does little for someone already there. Their analysis looked at all the benefits that might come from a buried highway — lower pollution, increased population, higher property values — and concluded that a hypothetical I-95 burial might cost $2.25 billion and produce a benefit of $3.5 billion. (The translation from economic paper to the real world might not be so smooth. Boston’s Big Dig, a highway-burying project that actually took place, ended up costing the city $14.8 billion, more than five times the project’s original $2.8 billion budget.)

While it’s safe to assume that I-95 isn’t getting buried anytime soon, Brinkman and Lin aren’t the only ones thinking about alternatives. In addition to the cap park, the DRWC recently proposed a pilot project that would see a trolley run along Columbus Boulevard from Race Street to Washington Avenue. That stretch already has tracks running down the median and would be a chance, according to DRWC president Joe Forkin, to wrest back some of the control cars currently have along the waterfront. Forkin isn’t stopping there, either. He sent a letter to PennDOT last year outlining all the changes he’d like to see in their designs for I-95. “The best outcome would be a recognition of where we are in time,” Forkin says. “We would like to see the auto-centric nature of it dialed back.” But even for someone like Forkin, who emphasizes that he has a positive relationship with PennDOT, getting feedback turned into changes is no sure thing. When PennDOT does tweak its plans, these modifications can seem more like gestures of goodwill on the agency’s part, rather than capitulating to any kind of pressure. At the end of the day, as a state agency, PennDOT simply isn’t all that accountable to local interests.

Maybe the greatest irony of the I-95 uproar is that it’s actually possible to imagine a scenario in which PennDOT gets its wish for a modernized highway and Kapczynski gets to realize his dream of better-quality fields for SEYAA. In PennDOT’s high-impact scenario for the Whitman Interchange, the fields do indeed have a new road running through them. But according to PennDOT’s own renderings, the plan would also create a direct connection between I-76 and I-95, which as a result would clear up acres of space to the east of the fields that is currently occupied by a winding maze of on- and off-ramps. You don’t have to squint too hard to imagine Kapczynski’s suburban-esque fields nestled in this newly created green space.

This solution wouldn’t be without its obstacles. A promise of better fields at some future date means little, McAfee points out, if today’s kids are kicked off their fields. Still, the fact remains that a compromise could be hiding in plain sight. But for some reason, PennDOT hasn’t raised this possibility with the community — and if it were to do so now, it seems unlikely that anyone in Whitman would believe them. When I floated this idea with Kapczynski, he said flatly, “That’s bullshit. There’s no space to go if this is taken away. None. And I’ll challenge anybody that tells me otherwise.”

PennDOT has pledged to hold another community meeting in the spring to discuss the status of the planning. The ensemble of civic associations intends to present PennDOT with their own community-outreach findings then. By the time of the meeting, kids will be starting their 31st season at the SEYAA fields. All around them, cars will be speeding, turning, traversing, connecting from one highway to the next.

If all goes according to the timeline, PennDOT won’t even begin to start construction for another 10 years — at the earliest. What’s clear, even at this incipient stage, is that the battle lines have been drawn. “We’re against expansion, we’re against capacity-building for the highway, we’re against things that would be detrimental to our community and environmental goals in South Philadelphia and beyond,” says State Senator Saval. As for PennDOT, they have a “clear mandate to reconstruct the highway, and from their point of view they feel certain basic things have to be done,” says Ruben, the chair of the citizen-led waterfront advocacy group. Ruben doesn’t begrudge PennDOT this. “I don’t feel their view is irrational. And I don’t feel that it comes out of malice or ill will. It’s just at the very least an incomplete vision and at worst totally misguided.” The open question is this: How much can that vision change? If the answer is Not very much? “Then people aren’t gonna stand for it,” Ruben says. “PennDOT may get it anyway, but they’re not going to get it without a fight.”

Published as “Highway to Hell” in the March 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.