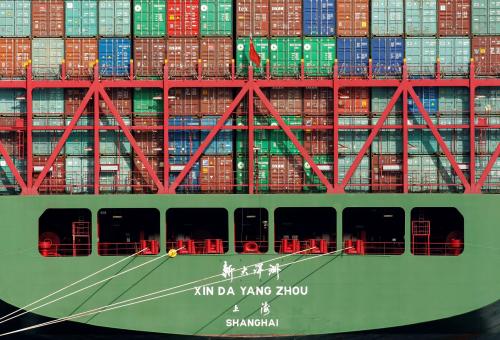

Since coming into office, the Trump administration has twice increased tariffs on Chinese imports into the United States by 10%, ostensibly because of China’s outsized role in supplying fentanyl precursors to the United States. Beijing has swiftly responded with a mélange of coordinated retaliatory measures—including imposing export controls on critical minerals, levying tariffs on U.S. agricultural products, putting U.S. companies on China’s unreliable entities list, announcing investigations into other U.S. firms, and filing suit at the World Trade Organization (WTO). Taken together, China’s responses seem designed to demonstrate resolve while not foreclosing the prospect of negotiations with the Trump administration.

What does China want?

As this tit-for-tat cycle continues, the most alarming outcome for Washington is not an escalation that pushes the relationship over the precipice. Beijing does not want that—and more importantly, President Donald Trump, U.S. businesses, and U.S. consumers do not want that either. Counterintuitively, the most dangerous outcome is a negotiation that ends in a “grand bargain” that goes beyond trade issues to encompass technology and security issues. Beijing’s overriding goal is for the United States to stay out of its way as it accrues power, wealth, and influence. In the negotiations that are likely to ensue in this trade war, Beijing would likely have three tiers of issues on which it would seek a rollback of competitive U.S. policies that have been at the heart of both the first Trump administration’s and then the Biden administration’s China policies.

First, Beijing would likely seek to loosen the scrutiny of China’s investments into the United States that intensified during the first Trump administration, and of the restrictions on U.S. investments into China put in place by the Biden administration. Beijing wants to go “back to the future” of the Obama years when two-way foreign direct investment spiked.

Second, Beijing would likely table trade-adjacent issues by seeking a rollback of the technology restrictions that the first Trump administration imposed on China and then the Biden Administration expanded and systematized. Even with those restrictions in place, Chinese companies like DeepSeek are still challenging the U.S. lead on crucial technologies like artificial intelligence, demonstrating China’s formidability and resilience as a competitor even in the face of its economic slowdown.

Third, since Beijing’s goal is to get the United States out of China’s way, Beijing could look to make progress on its long-standing objective of undermining U.S. security commitments in the region, especially in contested areas like the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. Beijing may calculate that it can appeal to Trump’s enduring suspicion of U.S. security commitments to get him to trade away U.S. pledges to defend partners in return for Chinese promises of future economic actions.

How will China approach trade negotiations?

Despite the real weaknesses in China’s economy, Xi Jinping will have some advantages in negotiations with the Trump administration. Most notably, Xi will find himself in the familiar position of a Chinese ruler considering a supplicant’s petition. Indeed, over the last 25 years, a fundamental imbalance has defined the U.S.-China relationship: whether prioritizing competition or cooperation with China, the United States constantly, and too often haplessly, beseeches China for help on a wide range of issues: North Korea’s and Iran’s nuclear ambitions; the flow of fentanyl precursors; Russia’s war on Ukraine; and perhaps most persistently, the nonmarket practices endemic to China’s economic policy. The laundry list of U.S. requests only grows longer as China extends its global reach, particularly because China seldom does much beyond pantomime a constructive role. The Trump administration should not expect Beijing’s approach to this coming round of negotiations to be any different.

We should also expect China to revive the defensive principle of “no concessions; no escalation.” In the first trade war, Beijing made few meaningful concessions to Washington, and as has been widely documented, never made good on the meager commitments it made in the Phase One trade deal. At the same time, Beijing largely prevented the trade war from expanding and meaningfully impinging on China’s macroeconomic trajectory. Moreover, Xi can afford to drag out trade negotiations for as long as is needed and may judge that the Trump administration will want some kind of deal or “win” to show for its efforts before the U.S. midterm elections next year. Xi and his team are likely very aware of this point—and of the fact that the first trade war concluded with Trump insisting that his team conclude a deal. Finally, unlike the first trade war, U.S. officials are unlikely to have a Chinese counterpart like Liu He—who had studied in the United States and was a well-known advocate for economic reforms. The most likely Chinese negotiator is Vice Premier He Lifeng, a Xi acolyte who lacks Liu’s reformist impulses and is more focused on implementing Xi’s economic policies than correcting them.

It is not clear that an even more expansive set of tariffs will prompt Xi to change course and undertake the reforms that the Trump administration wants to remedy the U.S.-China trade imbalances. Trump’s claims during the campaign that he would impose 60% tariffs on China inured China to the smaller tariffs announced thus far. Moreover, since Xi has eschewed much-needed economic reforms in the face of China’s existing headwinds, an external push seems unlikely to compel him. In fact, Xi may be even more loath to change course in response to outside pressure now that he is well into his third term. The three “D” problems afflicting China’s economy today—demography, debt, and deflation—have been born of decades of domestic dysfunction; they are not the result of U.S. trade actions.

How should Washington navigate these challenges?

Given these challenges, it would behoove the Trump administration to abide by four best practices as it prepares for tough negotiations with Beijing.

Be clear about your key objective. Whereas China has a clear objective going into the trade war—to do the bare minimum to get the Trump administration off its back on trade issues—it is still not yet clear what exactly the Trump administration wants to do. Many rationales have been offered, from a crackdown on fentanyl precursors to rectifying the trade imbalance to pushing Beijing to undertake structural reforms that would run counter Xi’s long-standing economic policies. Beijing is uncertain about the administration’s objectives, which has probably fed its reluctance to have Xi engage directly with Trump on these issues. Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s consideration of additional tariffs might seem from the outside that these are tactics without a strategy. Identifying clear, parsimonious, and mutually compatible objectives will help discipline the administration’s approach.

National security is non-negotiable. The administration should make clear to its Chinese counterparts early and often that issues related to national security are not up for discussion—particularly the U.S. regional military presence and the restrictions on high technologies that could advance China’s military modernization. This is the best way to realize the administration’s stated policy of “peace through strength.” The administration’s initial executive orders (EO) have revealed its position on some key issues that China might try to bring up in a negotiation. For example, the EO on American First Investment Policy calls for enhanced scrutiny of Chinese investments, while the EO on America First Trade Policy tasks the Departments of Commerce and State with identifying loopholes in existing export controls. The challenge seems to be that Trump may not be as committed to these positions as his staff—as reflected in his statement that would welcome more Chinese investment, and his rollback of sanctions on Chinese telecommunications firm ZTE during the first trade war.

Be prepared to walk away. As much as Trump likes to make a deal, he has demonstrated a willingness to walk away from a bad one—as he did in Hanoi during his meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. Rather than pursue additional iterations of the Phase One trade deal, which was meager in both conception and execution, Trump and his team should be prepared to walk away from the table. Demonstrating a willingness to walk away will upend Beijing’s assumption that the Trump administration needs a “win” from the trade war with Beijing before the U.S. midterm elections—thereby enhancing U.S. leverage.

Leave the haggling to staff. A major risk is that Xi is not Kim: if Trump were to walk out of a meeting with him, Xi may take it as a personal affront, leading to a collapse in bilateral diplomacy for a sustained period. The pause would likely rattle world markets and be even more prolonged and tense than the hiatus after the Biden administration shot down a Chinese spy balloon in 2023. The best way to mitigate the risk of such fallout—and to preserve the U.S. ability to walk away from negotiations without more dangerous consequences—would be for the administration to leave the details to Trump’s advisors and staff and preserve the president’s direct line to Xi to close the deal. Although Trump seems to want to negotiate directly with Xi, Xi is unlikely to want the same for fear that the conversation could break down into an embarrassing episode or mutual recrimination.

The Trump administration should be mindful that when it comes to such negotiations with China, even when you “win,” you lose. The risk for the administration is that, after a protracted negotiation, the United States gets a series of Chinese promises to reform its nonmarket practices—much as Beijing promised when it entered the WTO. And by the time anyone realizes that China has failed to implement any of those promises, the Trump administration’s time will be up—and China will begin the cycle anew with a new administration.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What Beijing wants from a US-China trade war

March 12, 2025