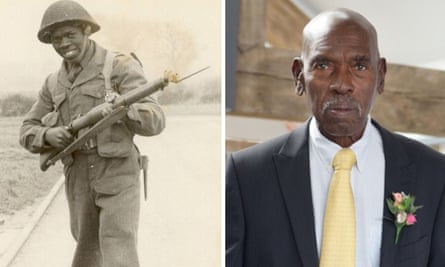

Harold Williams is a member of the Windrush generation who moved to the UK in 1955 and spent 40 years living and working there, including a stint in the army. But after he retired to Antigua, the country of his birth, in 1995, the UK government froze his state pension entitlement. Since then, he may have missed out on more than £30,000.

Monica Philip has a similar story. Now aged 81, she spent 37 years working in the UK before moving back to Antigua to nurse her ailing mother. She is having to manage on pension payouts that are little more than half what she would be getting if she had stayed in Britain.

Campaigners say there are many people like Williams and Philip who accepted the invitation from the British government to emigrate from the Caribbean but, decades later, have been “effectively cheated” out of their rightful pension because they wished to spend their retirement years in their country of birth or ancestry.

The issue could be put in the spotlight soon, with calls this month for a new official Windrush working group to look into the problem.

The injustices suffered by the Windrush generation have been well documented but a quirk in the pensions system means that some are facing another blow. If an individual moves back to – among others – Antigua, Trinidad, St Lucia or Grenada, their UK state pension is frozen for life.

By contrast, those who move back to Jamaica or Barbados, also Commonwealth Caribbean nations, are not penalised in this way. For retirees in Jamaica and Barbados, the British state pension increases in line with inflation, as it does for those who stay in the UK or move to an EU country, the US or one of a disparate list of countries including Israel and the Philippines.

Last month a cross-government working group was launched in an attempt “to address the challenges” faced by the Windrush generation and their descendants. This was two years after the then prime minister, Theresa May, promised to right the wrongs faced by those mistakenly classified as illegal immigrants by the Home Office.

Earlier this month, Philip wrote to the home secretary, Priti Patel, to ask for the group to review the policy of freezing the pensions of people who move back to certain Caribbean countries.

Philip is one of about 300 pensioners living in Antigua and Barbuda whose payments have been frozen. There are a further 1,300 living in Trinidad and Tobago, almost 1,000 in Grenada, more than 800 in St Lucia, and hundreds more spread across islands such as Montserrat, Anguilla, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and St Kitts and Nevis.

This is not an issue that only affects some older people who retire to the Caribbean. In all, there are about 500,000 Britons living in more than 100 countries around the world who are losing out as a result of the UK’s frozen pensions policy.

If you move to one of these countries from Britain, your basic state pension will be paid at the same rate as it was when you first became entitled to it, or when you left the UK if you were already a pensioner at that point.

Williams, who is 85, receives a UK state pension of £78.46 a week. If he had stayed in Britain or moved to a country where payments have increased, he would be receiving a lot more: the full UK basic state pension is £134.25 a week.

Born in Antigua in 1934, he relocated to the UK 21 years later and worked as a motor mechanic in Leicester. He served in the army before later working as a mechanic with the Post Office, a junior manager for BT and a driving instructor. Aged 60, he retired to Antigua and on turning 65 at the end of 1999, he started to receive his UK state pension.

Williams was never unemployed and paid taxes and national insurance all his working life. He says that while he would not say he was struggling financially, “I could do with the extra cash to assist in improving my standard of living” – particularly now he is paying $2,000 East Caribbean dollars (£585) a month to support his wife, who lives in a care home.

“I had no choice but to contribute to the system all of my working life, so why should I be treated differently from folks who have retired to Barbados and Jamaica?” he says.

Philip was born in 1938 and emigrated to the UK in 1959. She worked there for 37 years, including a spell at the Ministry of Defence, but had to return to Antigua in 1996. Her UK state pension, to which she became entitled in 1998, was £74.11 a week and has remained at that level ever since.

“This leaves me with a pension that is almost half of what I would receive if I had remained in the UK,” she says. “I do not believe I should be punished for returning to Antigua and Barbuda.”

Philip adds that the policy’s unfairness and arbitrary nature are shown by the fact that her sister still lives in the UK and receives a full uprated pension.

During a House of Lords debate in May, the Conservative life peer Lord Randall of Uxbridge described the frozen pensions policy as an injustice that “affects many of the Windrush generation and many others, too, throughout the world”.

In the past, ministers have conceded that the rules are illogical. However, they argue it would be too expensive to uprate the pensions of those affected – estimates suggest more than £500m a year – and money should be targeted at the poorest pensioners in the UK.

A government spokesperson says: “This issue of pensions is completely unrelated to issues experienced by the Windrush generation. The government continues to uprate state pensions overseas where there is a legal requirement to do so – for example, in countries where there is a reciprocal agreement that allows for uprating.”

The spokesperson added: “We are determined to right the wrongs of the Windrush generation, which is why the home secretary is driving change to implement the findings of the Lessons Learned review to ensure nothing like this will happen again.”

Find out more about the campaign at endfrozenpensions.org

How the policy works

The UK’s frozen pensions policy dates back to just after the second world war and has been a source of complaints for decades.

The general position is that the state pension is payable overseas but, where someone is not “ordinarily resident” in the UK, there is no entitlement to an annual increase. Their pension is frozen at the rate on the date they left the UK or when they became entitled to it if they were living abroad at the time.

However, increases are payable to pensioners living in countries with which the UK government has a “reciprocal social security agreement” that provides for them, as well as those living in the European Economic Area (EEA), plus Switzerland and Gibraltar.

The current list on the Department for Work and Pensions website includes Barbados, Bermuda, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Israel, Jamaica, Kosovo, Mauritius, Montenegro, North Macedonia, the Philippines, Serbia, Turkey and the US.

Confusingly, although the UK has social security agreements with Canada and New Zealand, you cannot get a yearly increase in your UK state pension if you live in either of those countries.

If a country does not appear in any of those categories, the UK state pension is not annually uprated there.

Criticism of the policy began to build during the early 1960s and over the years there have been legal challenges and campaigns but nothing has managed to overturn the status quo.

The government has said that post Brexit it will continue to annually increase UK state pensions for Britons living in the EEA or Switzerland by 31 December 2020 for “as long as they continue living there”.

However, the picture is a lot less clear for those who move to an EEA country or Switzerland from 1 January 2021 onwards, as this is part of the current negotiations with the EU.

What you can get elsewhere

If you move to a country where the UK state pension does not increase, you may find you are entitled to a pension or other benefits under its own system. But the rules can be fiendishly complicated and there will often be restrictions on what you can get.

For example, in Australia there is the Age Pension for those aged 66-plus but this is means-tested and British migrants are not eligible until they have been an Australian resident for at least 10 years. The maximum basic rate for a single person is A$860.60 (£478) a fortnight but the income and assets tests carried out may well greatly reduce what you receive.

In Canada the Old Age Security (OAS) pension is a monthly payment available to those aged 65-plus who meet the country’s legal status and residence requirements. To get it, you need to have lived in Canada for at least 10 years since the age of 18. What you receive will depend on how long you have lived there after the age of 18. For example, if you have lived there for 40 years or more, you will qualify for the full OAS pension.